By Vincent Beiderbecke, California State Library, Information Technology Bureau

Recently library staff unfurled a giant map showing the California County Free Libraries of 1915 in BTBL’s sorting area. The map had been stored on top of BTBL shelving for quite some time before it was decided to take it down and examine its condition. Taking the map down and unrolling it required several staff due to its immense size and weight.

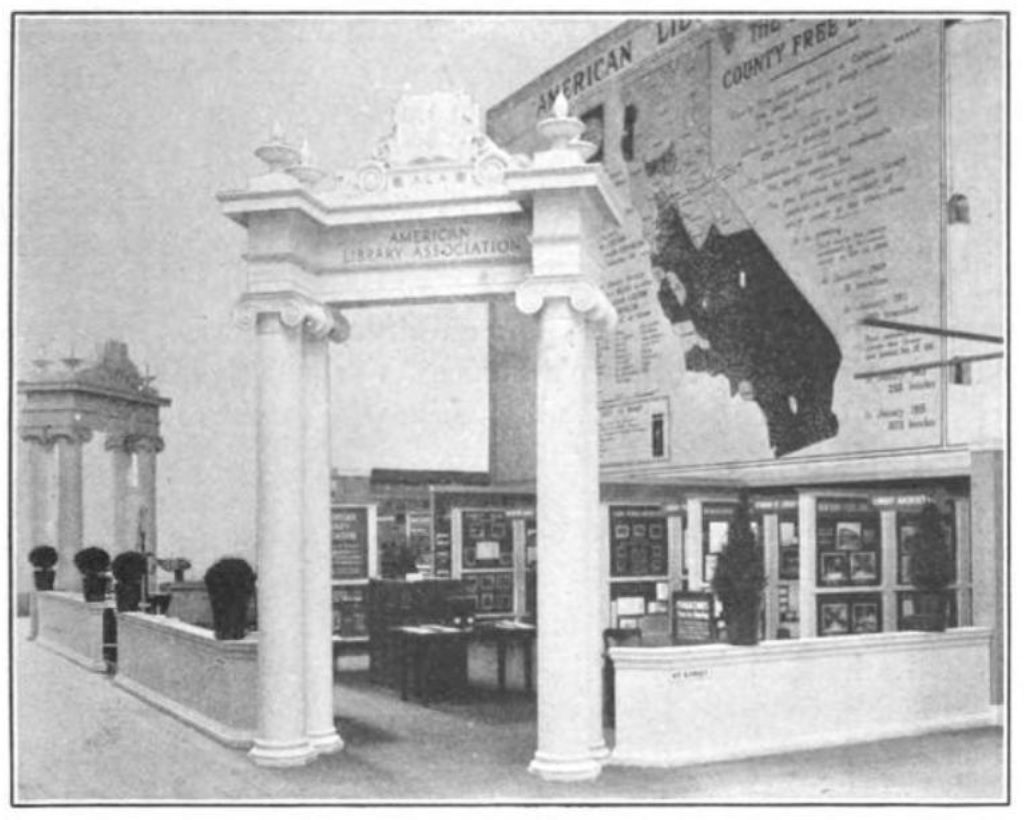

The same map was also displayed in the Palace of Education at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition. The ALA committee in charge of the various library exhibits at the Exposition included James Louis Gillis, who served as California State Librarian from 1899 until his untimely death in 1917. Gillis also established California’s county library system in 1909.

History of the map

The PPIE exhibit map was a collaboration of The California Library Association and the California State Library. The agencies proudly announced they “united their displays with that of the A.L.A. The outstanding feature of the California exhibit is a great map, forty feet square, representing the present state of the California county library system. This shows at a glance the scope of the system, and the method by which the relations between the counties and the State Library at Sacramento are maintained. This map was made by Mr. Charles [Sumner] Kaiser, architect of the booth containing the exhibit.”

Digitizing the map

After laying the map out on the floor and seeing it was in good condition, it was decided that the map should be digitized. To avoid disturbing BTBL’s daily operations, the project had to be done over the three-day holiday weekend. Matt Bartok, James Crudup, and I were charged with the difficult task of moving all of our camera equipment down to BTBL, digitizing the map in high resolution, and moving everything back out of BTBL before Tuesday.

Digitizing an object of this size presents us with many technical challenges. To ensure that all of the small details are properly captured for archival quality, the map needed to be photographed in many multiple pieces, or “tiles” that will be stitched together later in Photoshop. We don’t have a lens wide enough to capture the map in a single image. Even if we did, the resolution and quality of the single image wouldn’t be nearly enough to resolve any fine detail.

Matt and I devised a system of consistent, repeatable lighting by placing a boom-mounted flash on a movable dolly that rolls on aluminum pipe. The camera stand and flash dolly can then move in sync with each other across the width of the canvas. Once a row is completed, the canvas is rolled down and the camera stand, pipe, and dolly have to be moved back as well.

Because we are only able to use one flash, another process must be done to even out the lighting. We correct for light falloff by photographing a clean sheet of foam core that is held right above the canvas. A program called Equalight is able to read the light pattern on the foam core and equalize the lighting for each tile we shoot. Without doing this crucial step, the edges of each tile will be obvious when stitching and is very difficult to blend together.

Another important step to ensuring archival quality is a process called Zig-Align. When photographing artwork, the sensor of the digital camera must be perfectly parallel to the subject. If the two are out of alignment, the image geometry will become skewed, and the four corners of the image will not be equally sharp. This will prevent successful stitching later on. A mirror is placed on the floor as well as on the camera’s lens. When looking through the viewfinder, a series of concentric rings should appear that form a “tunnel” that runs to infinity. Once complete, it is accurate to the width of a piece of paper. The Zig-Align process is repeated for each row we shoot to ensure the camera is still in alignment.

All in all, forty-three tiles were captured at thirty-six megapixels of resolution per image. For the stitching process to be as accurate as possible, forty-percent overlap between images (both horizontally and vertically) is necessary.

I would like to gratefully acknowledge both Matthew Bartok and James Crudup. This project would not have been possible without their numerous talents and incredible dedication to the project. Matt’s technical photographic expertise was vital in figuring out how to digitize an object as massive as this. James’ Herculean strength was absolutely crucial in moving and positioning a thousand pounds of camera equipment as well as the map itself, which weighs several hundred pounds. We worked arduous 13-15 hour days over a three-day weekend to get the map digitized. Also, many thanks to BTBL for letting us use their facilities to digitize this incredible piece of California history.

Vincent Beiderbecke